Description

In the next decades, the hospital as we know it today may very well become extinct, and the meaning of the term may change dramatically. This has happened many times in the past. This brief history of hospitals as a typology and its previous transformations will serve to highlight the exceptionally dynamic character of the building type.

Hospitals as Charitable Institutions

Why concentrate people suffering from disease in a single building? The belief that special facilities might benefit their health extends back to Antiquity. The Greeks had asklepieia, complexes consisting of various buildings with a temple as their nucleus. Nursing patients was one of their main objectives. The Romans introduced valetudinaria in order to treat sick and wounded soldiers and thereby to help preserve the military and economic power of the state. The goal of improving the health of the people who came to the asklepieia and the valetudinaria was eclipsed when Christians began to conceive of healthcare as a responsibility of the Church. In 325 AD the Council of Nicaea declared that every town should have some place to take care of the sick. This resulted in the creation of the xenodochium, a combination of the basilica — basically a church — and the valetudinaria. The council of Aix-la-Chapelle, in 816, urged the Church to create charitable institutions for the poor to offer them help. And that help was given by hospitals, which were closely linked to the Church. This explains the use of the French term hôtel-Dieu. The most famous was the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris. Architecturally, the most interesting one is in Beaune (1443–1451), which still exists but has long since ceased to care for the ill. In addition to this, there were monastic hospitals, for example in Tonnerre (1293) and Angers (1153). All of these places were charitable institutions helping the poor, not hospitals in today’s sense of the word.

Hôtel-Dieu, Tonnerre, France, 1293, floor plan. Conceived as a charitable institution for the poor, this type of hospital offered its inhabitants mainly a large hall filled with many beds. Healing patients was not the primary goal, and though medical doctors offered their services, they often could do little to cure patients.

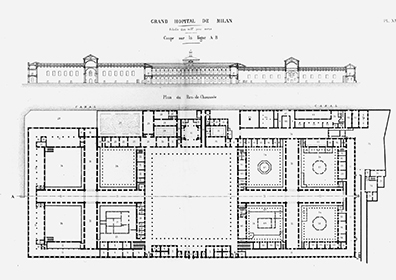

The rise of cities in the 13th century, first in Italy and Flanders, then elsewhere, stimulated the development of non-religious forms of healthcare. Brunelleschi’s Foundling Hospital in Florence is credited with being the building that ushered in Renaissance architecture, but its Milanese counterpart is better known.[1] The Ospedale Maggiore, designed by the architect Antonio Averulino, known as Filarete, was founded in Milan in 1456 and replaced a number of smaller structures. The highly innovative Ospedale Maggiore is not only one of the first hospitals built according to the geometric design principles of the Renaissance; it also turned to secular medical doctors to expand the range of the hospital services beyond the limited scope of what the clergy could offer. Remarkably for that period, Filarete even paid attention to the building’s hygienic conditions. In this period cities usually also took care of people suffering from contagious diseases, often erecting simple barracks for them outside the built-up areas in an effort to prevent further spread of the disease.

Ospedale Maggiore, Milan, Italy, Filarete, 1456. A unique example of renaissance architecture, the Ospedale Maggiore was a civilian institution that challenged the quasi-monopoly of the church and became one of the first hospitals that paid attention to hygienic conditions.

In the 18th century, the state joined the churches and cities as a supporter of hospital construction. Viewing its population as one of the main pillars of its prosperity and military power, the state focused primarily on the construction of military hospitals, a strategy that recalls the thinking behind the Roman valetudinaria.

Royal Hospital Chelsea, London, UK, Christopher Wren, 1682. Built for wounded navy officers, this hospital was initiated by the state, which hired one of the country’s most esteemed architects. Wren designed a spacious building with a large central court.

Royal Naval Hospital, Greenwich, London, UK, Christopher Wren, 1694. In the wake of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the rise of the empire also saw the continuous expansion of the navy and all its institutions.

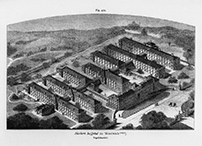

The Chelsea Hospital in London (1682) and the Greenwich Royal Naval Hospital (1694), both designed by Sir Christopher Wren, paved the way for the pavilion hospital. The wings in the Naval Hospital were divided into two separate wards that were connected on two sides. Alexander Rovehead took a further step in his design for the Royal Naval Hospital at Stonehouse near Plymouth (built 1756–1764) by splitting the wings into separate pavilions. The courtyard was left open, facing the seaside.

Royal Naval Hospital, Stonehouse near Plymouth, UK, Alexander Rovehead, 1764. One of the first pavilion hospitals, Rovehead’s design was an early example of what became the dominant hospital type in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

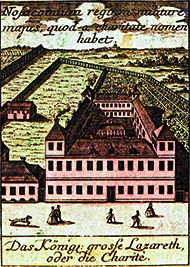

Civilian hospitals also increasingly became instruments of health policy at the local level. Unlike the military hospitals, they focused on the poor. In some cases, their inhabitants were obliged to work: rounding up idle paupers from the streets, these institutions served security and economic purposes as much as they dispensed charity. Within just a few decades, dozens of them were built, especially in the German-speaking countries, which is also where corridor hospitals first appeared. Even though the latter were usually relatively small, their design echoed that of other representative buildings. The Inselspital in Bern, Switzerland, was the first of this type. Designed by Franz Beer and built between 1718 and 1724, its wards were situated on either side of a long corridor. Open spaces gave this relatively small building, which could accommodate only 45 patients, a friendly, airy appearance.[2] The Charité in Berlin, an institution meant to accommodate 200 patients, followed its example. Founded in 1727, it was much larger and based on an almost square floor plan. Here, the corridor ran around an open courtyard and connected the wards, which had ten to 12 beds each, on the outside. This model culminated in the Allgemeines Krankenhaus in Vienna, which was conceived by Joseph von Quarin, who worked there as a physician and who received assistance from the architect Josef Gerl in formulating the basic design principles. They opted to renovate an existing sanatorium, which was reconstructed to accommodate no fewer than 2,000 patients.[3]

Inselspital, Bern, Switzerland, Franz Beer, 1724. A characteristic example of a corridor hospital

Charité, Berlin, Germany, 1727. Originally a sanctuary for patients suffering of contagious diseases located outside the city’s border, it was soon transformed into a teaching hospital.

During the Renaissance, scientists began to question the traditional ideas about medicine that reflected the Middle Age’s religious concepts of the divine order of the universe, and empirical research slowly increased. Teaching hospitals developed, which tried to educate their students in the field of human anatomy. The heart of most teaching hospitals was the anatomical theater. The term ‘theater’ is no coincidence: seats or benches were arranged in tiers, although in most anatomical theaters the students surrounded the stage on all sides. Here, students saw how doctors dissected corpses and examined the internal organs of the human body. The oldest, which still exists, was built in Padua in 1594. For centuries, dissection was the only way to find out how the human body works. Specimens of specific organs were prepared and stored in glass bottles, and ultimately the accumulated results often filled entire rooms. Rudolf Virchow, who worked at the Charité in Berlin, is credited with revolutionizing pathological anatomy in the mid-19th century, establishing this field as the vanguard of medical research.

The Hospital as a ‘Machine à Guérir’ — A Healing Machine

Well into the 18th century, hospitals were places of charity, not medical institutions in the modern sense. Only in the late 18th century did curing the ill become their primary task. Medical doctors were not expected to play a substantial role in hospitals. The latter developed into technologically advanced facilities designed to provide their patients with clean air. It was generally believed that diseases were caused by so-called miasma, harmful vapors. Statistical analysis and medical cartography — two important scientific innovations — showed the link between the frequency and severity of diseases, on the one hand, and the physical conditions of the patients’ living quarters, on the other. The Allgemeines Krankenhaus in Vienna (1784) was among the first to use technology to improve the supply of fresh air and to dispose of air that was thought to be contaminated by contact with the patients.

Allgemeines Krankenhaus, Vienna, Austria, Josef Gerl, 1784. An early case of a large hospital made up of long buildings that form gardens. The patient rooms are situated on either side of a central corridor.

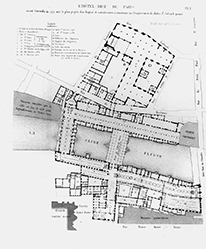

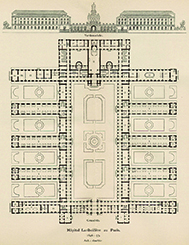

Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, France, mid-18th century (before the fire). After numerous extensions, the hospital had become a maze-like complex that crossed the Seine. Even so, its capacity fell short of the demand, resulting in overcrowding, abominable living conditions and a high mortality.

Taking into account scientific views on miasma and inspired by the technologies developed in the mining industry to ensure that the miners were supplied with fresh air, French designers developed plans that can be seen as the origin of the hospital as a specific building type. This innovation took place in tumultuous times: Paris on the eve of the French Revolution. The aims of the architects and planners partly coincided with those of the revolutionaries: they wanted to abolish a society based on religion and superstition and replace it by a rational order based on the laws of nature. When the Paris Hôtel-Dieu burned down in 1772, the time was propitious for replacing it by a hospital that no longer had any connection with the Church. Since the conditions of the patients in the old building had been disastrous, with the death rate running as high as 1 in 4.5, there was broad support for the introduction of new approaches. Between 1772 and 1788, more than 200 proposals were made. It was agreed that the buildings most likely to foster the recovery of patients would be based on recent advances in the natural sciences. They were soon labeled ‘machines à guérir’, healing machines, and were designed, above all, to provide abundant fresh air.

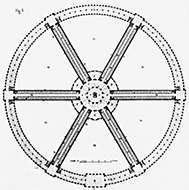

Design for the Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, France, Antoine Petit, 1774. After part of the hospital burned down, enlightened medical doctors and architects joined forces and produced a remarkable number of revolutionary hospital designs that identified healing people as the institution’s primary mission. Providing fresh air was the aim of most models, among them this circular ‘radial’ type.

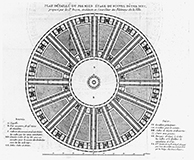

Design for the Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, France, Bernard Poyet, 1785. An alternative ‘radial’ plan

In 1774, Antoine Petit presented a radial plan where each of the six spokes functioned as a kind of wind tunnel. In the center, Petit projected a round building topped by a cone-shaped vent, a form he derived from a glass-making furnace that had been published in the Encyclopédie.[4] Bernard Poyet, a state-employed architect, and Claude-Philibert Coquéau presented a radial plan for a colossal hospital on the Île des Cygnes, which they published in the Mémoire sur la nécessité de transférer et reconstruire l’Hôtel-Dieu de Paris (1785).[5] The plan, which was structured like a large fan, had 16 wings and a total capacity of more than 5,000 beds.

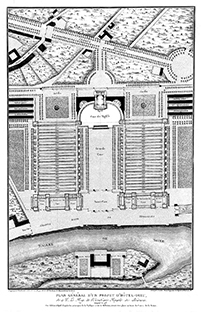

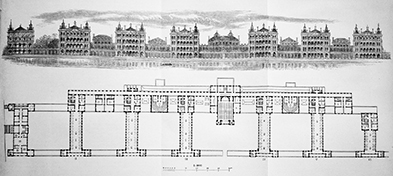

Design for the Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, France, JeanBaptiste Le Roy, Charles-François Viel, 1773. The alternative for the circular hospitals was the pavilion type which, already tested in England, became the dominant model.

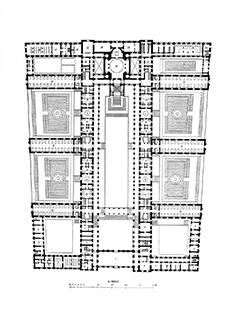

The ideas behind these circular ‘ventilators’, which were intended to be erected in natural surroundings outside the city, were challenged by other architects, who favored rectangular plans. The latter could more easily be incorporated in an urban environment, which is where the hospital was supposed to finds its clients: the urban poor. Jean-Baptiste Le Roy, a physician who had been working on his own plans since 1773, asked the architect Charles-François Viel to give architectural form to his concept of separate pavilions. Viel designed a symmetrical pavilion hospital, in which 11 wards were arranged in parallel, on either side of a great court, with smaller courts in between them. The design was published in 1789 in Leroy’s Précis d’un ouvrage sur les hôpitaux, which contains one of the first explicit references to a building as a machine. According to Leroy, a hospital should be ‘une machine à traiter les malades’.[6] In his report he referred to tents in a military camp and, in a gentler vein, the pavilions in the garden of Chateau Marly (1679), designed by Jules Hardouin Mansart. To ensure the constant flow of fresh air, the pavilions’ roofs took the form of mine shafts.[7] The pavilion type was recommended by the committee of the Académie des Sciences and soon accepted as the ideal for the layout of hospitals. However, it would take more than 40 years before the first hospital of this type was realized. That was the Hôpital Lariboisière (1839–1854) by Martin-Pierre Gauthier, who was instructed to base his design on the recommendations of the committee of the Académie des Sciences.[8] Lariboisière was an immediate success and it was published all over Europe and the United States.

Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris, France, Martin-Pierre Gauthier, 1839–1854. Many years after the conception of the pavilion hospital, this hospital represents the first important example that was actually built.

Why did it take so long for the recommendations of the above-mentioned committee to be realized? As before, innovations in military healthcare paved the way for the civilian sphere. During the Crimean War (1854–1856), the British army erected field hospitals that were made up of separate barracks. Florence Nightingale advocated this arrangement and explained its advantages in her Notes on Hospitals (1859). In England her efforts resulted in the realization of the Royal Herbert Military Hospital in Woolwich (1859–1871), designed by Douglas Galton, and the St. Thomas Hospital in London (1866–1871), designed by Henry Currey. Perhaps the most perfect pavilion hospital was the one erected in Paris, which opened its doors more than 100 years after the fatal fire of 1772. The new Hôtel-Dieu, designed by Emile Jacques Gilbert, was situated on the northside of the square in front of Nôtre-Dame Cathedral. The site was suggested by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, who was responsible for the urban reconstruction that gave Paris its famous boulevards.

Royal Herbert Military Hospital, Woolwich, UK, Douglas Galton, 1859–1864. Stretched pavilions that resemble a corridor hospital layout are separated by gardens and connected through a central corridor.

St. Thomas Hospital, London, UK, Henry Currey, 1866–1871. A comb-like structure that combines a number of relatively large, multistoried pavilions.

Hôtel-Dieu, Paris, Emile Jacques Gilbert, 1866–1876. This building replaced the medieval Hôtel-Dieu.

Starting at the end of the 19th century, most of the hospitals built in Europe and the United States adopted the pavilion system. This allowed light and fresh air to flood the patient wards, which, moreover, were often surrounded by lavish gardens. The pavilion system was exceptionally flexible: a hospital could start with a few pavilions and gradually expand by simply adding new ones. One of the first examples of the type in Germany was the Städtisches Krankenhaus am Friedrichshain in Berlin (1868–1874), designed by the architects Martin Gropius and Heino Schmieden. The Städtisches Krankenhaus in Hamburg-Eppendorf, built between 1884 and 1889 after a design by Carl Johann Christian Zimmermann and Friedrich Ruppel, consisted of more than 50 pavilions. The latter example brings up one of the major disadvantages of the system: at a certain point, when more pavilions are added, the distances between them and centralized facilities like the laundry and the kitchen can become too great for the institution to operate efficiently.

Städtisches Krankenhaus am Friedrichshain, Berlin, Germany, Martin Gropius and Heino Schmieden, 1868–1874. A typical example of a pavilion hospital in Germany, it was designed by two architects who began to specialize in hospital architecture.

Städtisches Krankenhaus, Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany, Carl Johann Christian Zimmerman and Friedrich Ruppel, 1884–1889. This complex shows the limits of the pavilion type: the distances between the buildings become too large to run the facility effectively.

Even though both the radial and the pavilion type had been conceived to fulfill functional requirements that were unique to hospitals, there was nothing specific about the latter’s interior spaces — hallways, rooms and offices. This began to change when surgery gained importance, enabled by Crawford W. Long’s introduction of ether as an anesthetic in 1846, and Ignaz Semmelweis’ demonstration, in 1847, of the crucial importance of hygienic measures. He showed that washing hands reduced mortality caused by puerperal fever to 1 %. Following Semmelweis’ lead, Joseph Lister began to experiment with carbolic acid in 1867 and demonstrated that it diminished the danger of infection. Hospitals housed the only facilities that could properly accommodate surgical procedures. Thus the operating theater became the first functional unit that could be found only in these buildings and nowhere else, as the example of Brooklyn Navy Yard Hospital demonstrates. Operating theaters were characterized by the use of large areas of glass, which allowed surgery to be performed in daylight; often, the glass walls faced north to eliminate direct sunlight and sharp shadows. Surgery also transformed the perception of the institution: ‘By the 20th century, for the first time in history the risks of going into hospital were less than receiving treatment outside its walls, primarily because hospital infections were being brought under some control.’[9]

Operating room in Brooklyn Navy Yard Hospital, New York, USA, ca. 1900. Only when hygienic measures and the invention of anesthesia transformed surgery, did the hospital develop spaces that were specific and could not be found anywhere else – the origin of what was later coined the ‘hot floor’.

The Hospital as a Medical Institution

With the introduction of medical technology such as X-ray machines around 1897, hospitals developed into medical institutions. Thanks to their use it became possible for the first time to ‘see’ inside the living body. Such expensive equipment had to be used efficiently and needed trained staff, and within a few decades hospitals developed a monopoly on medical technology. Medicine achieved considerable progress in the 19th century and hospital typology changed. The discovery of bacteria by Louis Pasteur proved that polluted air was not the major problem it had long been thought to be. Therefore, there was no longer a compelling reason to construct hospitals as pavilions and more compact hospital typologies evolved.

High-Rise Hospitals

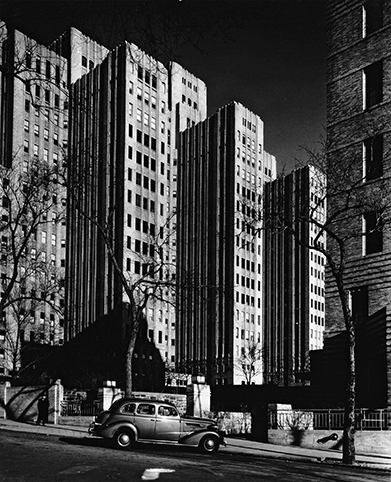

The most impressive of these compact types appeared in the United States. High-rise hospitals were a response to the ever-increasing scale of the pavilion type and, in American cities, the high cost of land. Major high-rise hospitals were the Columbia University Medical Center (Presbyterian Hospital), designed by James Gamble Rogers (1926–1930), and the Cornell Medical Center in New York (1933), designed by Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch and Abbott.

Cornell Medical Center, New York, New York, USA, Coolidge Shepley Bulfinch and Abbott, 1933. The opposite of the pavilion type, the high-rise hospital developed in the United States is very compact. Since the discovery of bacteria, polluted air was no longer seen as the primary cause of diseases and the pavilion type was perceived as obsolete.

Columbia University Medical Center (Presbyterian Hospital), New York, New York, USA, J. Gamble Rogers, 1930. This high-rise complex is one of New York’s iconic hospitals of the era.

In Europe, only a few high-rise hospitals were built before World War II. Paul Nelson designed a large health center for the French city of Lille, which combined a medical school, a clinic, a hospital, a nursing home for the elderly and an apartment building. The complex, inspired by the Presbyterian Hospital of Columbia University, was touted as a ‘health city’.[10] It was never built, however, and was replaced by a project conceived by Jean Walter, who had made his name as the architect of the Beaujon Hospital in Clichy, Paris (1933–1935). Built between 1935 and 1953, Walter’s plan was characterized by a rigorous separation of internal traffic flows. This had logistical advantages and also affected the scale of the building, which, although immense, was divided into a number of wings that spread out from a central core.

Design for the Cité hospitalière, Lille, France, Paul Nelson, 1933, model view. This example of a large-scale, compact hospital celebrates modern medicine in a building that radiates a modern, rational atmosphere but remained unbuilt.

Hôpital Beaujon, Clichy, Paris, France, Jean Walter, Louis Plousey, Urbain Cassan, 1932–1935. This European version of the American high-rise compact hospital established Walter as a specialist in healthcare architecture.

To lower costs and improve logistical efficiency, the Swedish architects Hjalmar Cederström and Gustav Birch-Lindgren developed a type that revolved around nursing units of 25 to 35 patients, with rooms accommodating one, two, four or six beds. These units were concentrated in an eight-story complex. Outpatient departments and treatment areas were located in separate but parallel wings, which made it easy to connect them. The Södersjukhuset (1944), architecturally a more straightforward building, inspired similar projects in several European countries. The nursing unit could be repeated as many times as was needed to arrive at the desired number of beds. A similar development can be seen in the Bürgerspital in Basel, designed by Hermann Baur in 1937. Here, the nursing wards, which all together could accommodate 1,000 patients, consisted of 16-bed units, which were in turn divided into two six-bed and two two-bed rooms. There was a clear distinction between the nursing areas on the one hand, and the treatment, research, laboratory, administration and university areas, on the other. Exploiting the pleasant California climate, Erich Mendelsohn concentrated the patient rooms of his Maimonides Hospital in San Francisco in a high-rise wing with rooms that gave access to balconies.

Södersjukhuset, Stockholm, Sweden, Hjalmar Cederström and Gustav Birch-Lindgren, 1944. The architects’ main design principle was a clear distinction between the hot floor, the outpatient department and the patient wards; they are often credited for introducing the nursing unit.

Bürgerspital, Basel, Switzerland, Hermann Baur, 1937–1946. An example of synthetic modernism, this is one of the first H-shaped hospitals.

Maimonides Hospital, San Francisco, California, USA, Erich Mendelsohn, 1946–1950. This hospital combines the open, sun-flooded architeture of California with the abstract architectural features of European modernism.

New Configurations T-Type, K-Type, H-Type

Given the rapid post-war population growth, an unprecedented increase in the demand for hospitals ensued throughout Europe and the United States. Since demand was expected to keep growing, the need arose for a type of building that could be substantially expanded without creating logistical chaos.

Continuing the innovations made at the Södersjukhuset and the Bürgerspital, a number of ‘alphabet’ types were developed, such as the T- and the K-type.[11] A simple version is the T-type, with the treatment areas in the vertical element. Jan Piet Kloos’ Diakonessenhuis in Groningen (1965) is an example of the K-type, with its characteristic bend in the patient wards, which since they face south, appear to embrace the sunlight.

K-type hospital, Diakonessenhuis, Groningen, the Netherlands, Jan Piet Kloos, 1965

The H-type, where one of the parallel wings accommodates the treatment spaces and the other one the patient ward, was inspired by Swedish and Swiss examples. Often, the treatment areas are divided into an inpatient area for those staying overnight in the hospital and an outpatient department for those leaving soon after receiving treatment, each part accommodated in a separate wing. The separation of wings with different functions obviously facilitates future expansion, since construction work in one part of the institution would not automatically lead to problems in the others.[12]

H-type hospital, Julianaziekenhuis, Terneuzen, the Netherlands, Jan Piet Kloos, 1954. This H-shaped composition offers a clear distinction between the main departments.

From the late 1950s on, the Breitfuß or ‘wide foot’ model rose to prominence (also known as hôpital arbre, socle-tour or in Britain as a ‘matchbox on a muffin’, that is a tower on a podium.) The assumption that patient wards do not need to be constantly refurbished and reconstructed, whereas technological innovations make changes in the treatment areas almost routine, resulted in the combination of a stretched-out, low-rise building of at most three floors and a patient ward in the form of a high-rise tower or slab on top of it. Inventions in the building industry facilitated the construction of very deep ‘muffins’: ‘With the aid of air conditioning and deep-span frame structures it becomes possible to plan a hospital like a department store, in one continuous floor, occupying the whole of the site.’[13] The Breitfuß — the German epithet became its informal name — was first developed in the United States, where it was introduced in a number of military hospitals before becoming the standard type for all hospitals for a considerable time. Gordon Bunshaft is credited with being among the first to explore its advantages — at the Fort Hamilton Veterans Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. In Europe, one of the first of this type was the Franco-American Memorial hospital at Saint-Lô (1945–1954), designed by Paul Nelson. An English example, inspired by the work of the Nuffield Provincial Trust’s Studies in the Function and Designs of Hospitals, is the Princess Margaret Hospital in Swindon, commissioned in 1953 and designed by Powell and Moya with Llewelyn-Davies Weeks.[14]

Franco-American Memorial Hospital, Saint-Lô, France, Paul Nelson, 1945–1954. This hospital is credited for introducing the Breitfuß model in Europe.

Princess Margaret Hospital, Swindon, UK, Powell and Moya with Llewelyn-Davies Weeks, 1953–1966. In the 1950s, the Nuffield Trust in England advocated a scientific approach to hospital architecture, inspiring projects like this hospital.

The expectation that the wards would shrink while the outpatient departments rapidly expanded called for types that could accommodate changes without expansion of their footprint. This led to a return to low-rise hospitals, since reconstruction was now seen as inevitable in all parts of the building including the patient wards. One of the first to explore the flexibility of low-rise structures was Hvidovre Hospital, Denmark. The reappearance of the low-rise types coincided with the emergence of counter-cultural criticism in the 1960s (which accused the high-rise hospital of representing an ‘authoritarian’ approach to medicine and called for patient-centered care) and structuralism in architecture. Ideally, the scale of hospital structures should be in harmony with the urban fabric of the area in which they are sited, but most new hospitals were built with a complete disregard for the local urban context. An example of a building that translates the structuralist approach often found in low-rise complexes into one built on a much vaster scale is the Academic Medical Center (AMC) in Amsterdam, completed between 1981 and 1985 to the design of Architectengroep Duintjer in cooperation with Dick van Mourik. The architects made a clear distinction between permanent parts (the concrete structure), semi-permanent components and elements that are likely to change regularly, thus emulating the growth and transformation of historical cities. Another quality that the building shares with historical cities is the distinction between private and public parts; the latter form a spacious combination of covered streets and squares which provide for urban functions like shopping.

Academic Medical Center (AMC), Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Architectengroep Duintjer with Dick van Mourik, 1981–1985. A striking example of structuralism, this hospital combines a permanent structure with semi-permanent and flexible elements, allowing processes of change.

Comb structures and models that use an internal street to lend greater coherence to the complex also became quite popular. Other hospitals are organized around large halls, an early example of which is the Krankenhaus Neukölln, Berlin by Josef Paul Kleihues (1985–1986).

The End of Hospital Typology?

Typologies are based on the assumption that specific functions can best be accommodated in buildings designed specifically for them. The clarity inherent in this approach lost much of its appeal when rapidly growing hospital departments were located near departments that were expected eventually to need less space. A clever division into zones was one of the ways conceived to increase flexibility, along with the preference for oversized spaces, since that made it easier to adapt them to purposes other than the ones they were originally designed for. The idea was to overcome the limitations of customized buildings perfectly geared to their specific function — the essence of functionalist design — since they cause problems as soon as the functional requirements change.[15]

Recent research supports the view that small hospitals generate fewer logistical problems than large ones and that many hospital functions ought to be outsourced. One of the most widely accepted concepts among architects and hospital managers today is that of the core hospital, according to which only those spaces that are truly specific, that is, devoted to diagnosis and treatment, should be tailor-made, while all other parts can be designed on the model of other building types. The wards, for instance, can be designed as a hotel, and a considerable part of the outpatient department can be modeled on the kind of retail facilities that have both front and back offices. The next step could be to outsource all services that are not really needed on the site, such as the laundry, the kitchen, the laboratory, even part of the patient wards and the outpatient department. What remains is a ‘core hospital’. Thus, an entirely new hospital landscape may emerge in the future.

Footnotes

Derek Stow, ‘Transformation in healthcare architecture: from the hospital to a healthcare organism’, in Sunand Prasad, Changing Hospital Architecture, London: RIBA Publishing, 2008, p. 16.

A. H. Murken, Vom Armenhospital zum Großklinikum. Die Geschichte des Krankenhauses vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart, Keulen, 1988, p. 25.

A. H. Murken, Vom Armenhospital zum Großklinikum. Die Geschichte des Krankenhauses vom 18. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart, Keulen, 1988, p. 37.

Anthony Vidler, The Writing of the Walls. Architectural Theory in the Late Enlightenment, New York. Princeton Architectural Press, 1987, p. 60.

Claude-Philibert Coquéau, Mémoire sur la nécessité de transférer et reconstruire l’Hôtel-Dieu de Paris: suivi d’un projet de translation de cet hôpital, proposé par le sieur Poyet, architecte & contrôleur des bâtimens de la ville, Paris, 1785.

J. B. Leroy, Précis d’un ouvrage sur les hôpitaux dans lequel on expose les principes, résultats des observations de physique et de médecine qu’on doit avoir en vue dans la construction des édifices, avec un projet d’hôpital disposé d’après ces principes, Paris, 1787, p. 589.

Anthony Vidler, The Writing of the Walls. Architectural Theory in the Late Enlightenment, New York. Princeton Architectural Press, 1987, p. 60.

M. Armand Husson, Étude sur les hôpitaux considérés sous le rapport de leur construction, de la distribution de leurs bâtiments, de l’ameublement, de l’hygiène & du service des salles de malades, Paris, 1862, p. 8.

Martin McKee, Judith Healy, Nigel Edwards, Anthony Harrison, ‘Pressures for change’, in Martin McKee, Judith Healy (eds.), Hospitals in a Changing Europe, Buckingham: Open University Press, 2002, p. 43.

J. Abram, ‘The filter of reason: experimental projects, 1920–1939’, in J. Abram, T. Riley, The filter of reason, New York, 1990, pp. 52–62.

I. Rosenfield, Hospitals. Integrated Design, New York, 1947.

N. Mens, A. Tijhuis, De architectuur van het ziekenhuis. Transformaties in de naoorlogse ziekenhuisbouw in Nederland, Rotterdam 1999, p. 107.

Paul W. James, William Tatton-Brown, Hospitals: Design and Development, London: The Architectural Press, 1986.

Derek Stow, ‘Transformation in healthcare architecture: from the hospital to a healthcare organism’, in Sunand Prasad, Changing Hospital Architecture, London: RIBA Publishing, 2008, p. 16.

Robert Wischer, Hans-Ulrich Riethmüller, Zukunftsoffenes Krankenhaus. Ein Dialog zwischen Medizin und Architektur, Vienna: Springer, 2007, p. 15.

Originally published in: Cor Wagenaar, Noor Mens, Guru Manja, Colette Niemeijer, Tom Guthknecht, Hospitals: A Design Manual, Birkhäuser, 2018.