Description

The word ‘hospital’ refers to a wide range of very different facilities providing technologically advanced medical diagnostics and treatment. Apart from the classical type — a building or a campus with various buildings that comprise a single hospital organization —. there are ‘focused factories’ that specialize in specific diseases or conditions. These vary in size from single-doctor operations to large complexes dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of certain diseases. Sometimes, outpatient departments function as satellite clinics of large general hospitals; in other cases, primary care providers and general practitioners constitute an integral part of the hospitals’ services. Every healthcare system has its own particular way to distribute medical services.

However, due to the urgent need to improve quality and reduce costs, healthcare policymakers and those responsible for its financing are increasingly attempting to (re)distribute facilities more efficiently. From their perspective the primary question is: where is the best place to provide the best care at the right time at the lowest cost? In order to answer this question, we need to rethink healthcare in terms of a ‘stepped care infrastructure’ involving close cooperation between providers at different stages of the various therapies dispensed, including ambulatory care, rehabilitation, care for the chronically ill, psychiatry and hospices. In the last decade, many hospitals have begun to function as parts of network organizations in which specialized institutions collaborate intensively to achieve both high quality and economies of scale.

Debates about centralization versus decentralization, and the definition of the various types of facilities needed in the latter case, revolve around a number of recurring themes, with factors such as the type of disease in question, scale and travel times leading to different solutions. Which model provides better patient-centered, affordable care? What are the consequences of that choice for, say, the level of control that patients with chronic diseases have over their therapies? Are relatively simple and low-risk diagnosis and treatment best accommodated by primary care centers? Should complex care be concentrated at the regional level? Is integration of the standard services with elderly care and psychiatry advisable? Remarkably, the study of which strategies to employ when considering the redistribution of healthcare facilities appears to have been largely neglected. Indeed, until recently improving the quality of care usually meant building larger and more consolidated healthcare facilities. Clustering scarce and expensive resources at one location made sense and scale held out the promise of efficient delivery, while delivering healthcare and sharing information across distributed facilities was cumbersome and could pose a safety risk for patients.

At present, however, the constraints that made centralization desirable are fast disappearing. The idea of breaking away from massive complexes and replacing them with networks of mostly smaller facilities has gained worldwide acceptance; it initially appeared both in Europe and the United States in the early years of the 21st century.[1] Concentration of specialized care, on the one hand, and decentralization of medical consultation and less high-level medical intervention, on the other, is now considered a valid option — even in the Netherlands, a country with a traditional preference for large-scale facilities.[2]

As Pierre Wack noted, ‘Especially in times of rapid change, the inability to see an emerging novel reality can cause strategic failure.’[3] What are these novel realities? Certain forms of chemotherapy and complex diagnostics can now be self-administered by patients at home. If the artificial kidneys currently in development are successful, entire dialysis centers could soon be rendered unnecessary. Portable imaging devices and high-speed data networks are redefining radiology departments — radiologists working from home studying images sent by mobile CT scanners from dispersed locations close to patients’ homes could become commonplace. Innovations such as mobile stroke units are extending the emergency department’s reach to the patient’s doorstep. Absolutely essential in this regard is the acceptance and general application of the century-old principle of ‘a centralized medical record, stored in a single repository, and capable of traveling with the patient’, as developed by Dr. Henry Plummer and Mable Root at the Mayo Clinic in 1907.[4] The Internet has the potential to make information stored in medical records available anywhere at any time, thus enabling hospitals to function as networks of distributed facilities and bringing healthcare closer to individual communities. Improved understanding of diseases and the greater efficacy of specific treatments, combined with smaller, cheaper and easier-to-operate equipment will make it possible to create satellite diagnosis and treatment centers.

Obviously, all this does not mean that large, centralized hospitals should be seen as relics of the past. Teaching hospitals need to attain a sufficient scale to function efficiently as research and educational institutions. Complex care and the treatment of rare diseases requiring highly trained specialists and advanced infrastructure is best centralized. Likewise, acute and urgent care is best provided in centralized emergency centers that remain fully operational around the clock.

For all other healthcare facilities, the question that needs to be answered is: what is the justification for clustering specific health services in one particular building at one particular site? Demand, scale and location must be rigorously analyzed in the planning phase. Which trade-offs need to be made in determining which processes, and thus which facilities, to centralize, and which to distribute? One feature that all medical facilities share is that they are increasingly focused on intensive medical intervention, relegating all other therapies to organizations that can rely mainly on staff with less training. ‘The burden of proof’, John Posnett writes, ‘must be with those who propose concentration to quantify the expected benefits and costs and to explain the process by which benefits will be realized in practice’ as ‘(…) costs cannot generally be presumed to be lower or outcomes better in larger hospitals.’[5]

In Europe and the United States, there is a marked trend toward a distinction between relatively small community hospitals and hospitals that exercise a monopoly over complex, high-risk interventions. Judith Healy and Martin McKee dub the latter the ‘separatist’ hospitals; they provide ‘services that primary care practitioners and community-based specialists are unable (…) to undertake’.[6] They can be either large facilities that offer the full range of therapies (and are often teaching hospitals) or specialized, so-called ‘focused factories’ that concentrate on specific sets of diseases. If healthcare systems become more transparent, these specialty hospitals may become more popular, contends the Joint Commission in a report issued in 2008.[7]

The first set of factors influencing planning and composition relates to the context in which healthcare providers operate: geography, demography, government policies, preexisting infrastructure and the available resources. Indonesia, with 0.204 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants and a total population of more than 234 million people spread over 6,000 islands, has a different set of geographical and resource constraints on the distribution of healthcare facilities than Austria, a mountainous, landlocked country with 4.86 doctors per 1,000 inhabitants and a population of 8 million.

The affordability, and therefore the composition and distribution of healthcare facilities in Nigeria, with a per capita GDP of around US $ 1,500 per year, is obviously different from that in Norway, with a per capita GDP of around US $ 100,000. Aging populations with stagnant growth need different healthcare services and face different workforce constraints than relatively young and growing populations. Countries with comparable health indicators, such as the United States and Cuba, may have completely different healthcare policies and infrastructure. Life expectancy in Cuba is higher than in the United States, with less than a tenth of the latter’s healthcare costs per capita.

The second set of parameters defining the possibilities and constraints of decentralization concerns the hospital itself. Which part of the care path can a patient independently and safely manage and monitor at home and which part can be delivered by primary care providers? Is it really necessary to build outpatient departments at the same location as the high-tech and intensive care facilities such as operating and catheterization rooms and inpatient departments? Low-risk patients needing treatment for a specific diagnosis might be able to follow their complete care path at decentralized facilities that lack fallback options such as an intensive care unit, while high risk patients with the same diagnosis might need to follow at least part of their care path at a specialized center. In any case, the role of the hospital in the regional healthcare landscape also influences its composition, chiefly how the new facilities will complement or conflict with the existing healthcare facilities.

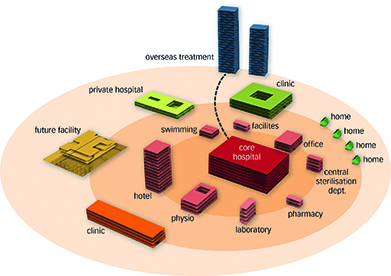

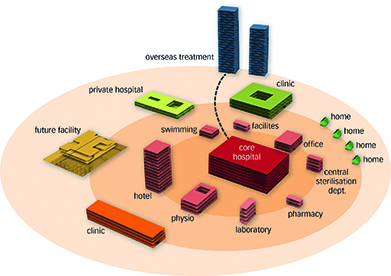

This way of thinking is not new. In 2004, the Netherlands Board of Hospital Facilities sponsored an ideas competition for the ‘Hospital of the Future’. The winning entry was by Venhoeven CS Architecten and Itten + Brechbühl. They approached the hospital as a collage of different functional elements.[8] Functionally, the inpatient departments are more similar to a hotel than they are to the rest of the hospital, and the many offices involved can be very similar to those in a normal office building. In other words, from a functional perspective most of the elements that make up a hospital are not specific to hospitals but rather generic; what is specific to hospitals amounts to no more than a third of the building, which may be termed the ‘core hospital’. The generic elements need not be designed differently from their counterparts outside the healthcare sector, and often these spaces form part of a well-advanced typology. Office expert John Worthington noted that the criticism of today’s new hospital construction could have been directed against office buildings 30 years ago and that there the problems in question have since been addressed.[9] More important, some of these office or hotel-like parts need not be located at the hospital. They could be peeled off, as it were, and transferred to other locations — hence the name for this concept in the Dutch healthcare sector, ‘schillenmodel’ (shell model).

Early example of the hospital as a collage of different functional elements. Winning entry by Venhoeven CS Architecten and Itten + Brechbühl for the 2004 Netherlands Board of Hospital Facilities’ ideas competition for the ‘Hospital of the Future’

The third question concerns operational logistics and specific local constraints. Is the projected diagnosis and treatment volume sufficient to ensure efficient operations at each facility? Distribution scenarios requiring personnel to travel between locations, for instance, are dependent on specific constraints. Travel is more acceptable in densely populated urban areas than in sparsely populated rural ones. Rural centers will, therefore, need to focus more on scaling their operations efficiently than do urban ones, asking for example whether a nurse practitioner or an ENT surgeon can be productive at the location for a whole day.

The availability of a reliable and secure digital infrastructure with failsafe backup systems is indispensable for the modernization of healthcare. Apart from electronic patient records, the analysis, redesign and monitoring of care pathways based on the information available in these records can become powerful management tools for the medical staff as well as, ultimately, for patients. Digitized care pathways can become the backbone for e-health applications that are now being developed throughout the world. It is important that the hospital organization ensures transparency and easy access to information. After all, Dr. Henry Plummer successfully introduced ‘a centralized medical record’ already in 1907, ‘stored in a single repository and capable of traveling with the patient’; it was managed using a system of pneumatic tubes.

The next step is to determine the scope and capacity of the program and the composition of the hospital building. This involves adding up the function and capacity prognoses, eliminating redundancy and developing ‘what-if’ scenarios. The result of this exercise is a range of function and capacity prognoses with varying levels of probability for the specific hospital building in question. This information is sufficient to determine the minimum capacity required for the core hospital. For instance, the conclusion might be: ‘this facility will be able to utilize efficiently at least 300 inpatient beds and ten operating rooms in all scenarios for the next 10–15 years. The number of additional beds varies between 20 and 100 and that of the operating rooms between two and four.’ Depending on its willingness to risk overcapacity, its financial resources and the potential alternative uses for the additional 20–100 beds and two to four operating rooms, the hospital can make a well-informed choice in the range of 300–400 beds and 10–14 operating rooms at that specific facility. From an architectural point of view, many generic components such as care facilities could become ‘invisible’ by decentralizing them. Generic buildings loosely distributed in the urban tissue could readily accommodate them.

Footnotes

Antonio M. Gotto, ‘Foreword’, in Richard L. Miller, Earl S. Swensson, J. Todd, Hospital and Healthcare Facility Design, New York, London: W. W. Norton, 2012 (third edition), p. 6.

Johan van der Zwart, Building for a Better Hospital. Value-Adding Management and Design of Healthcare Real Estate, Delft, 2014, p. 109.

Pierre Wack, ‘Scenarios: shooting the rapids’, Harvard Business Review, November 1985.

‘A century of medical records’, March 19, 2010. http://onhealthtech.blogspot.de/2010/03/century-of-medical-records.html; Dana Sparks, ‘Dr. Henry Plummer, Mayo’s ultimate renaissance man’, in Mayovox, April 1989.

John Posnett, ‘Are bigger hospitals better?’, in Martin McKee, Judith Healy (eds.), Hospitals in a Changing Europe, Buckingham: Open University Press, 2002, pp. 114, 115.

Judith Healy, Martin McKee, ‘The role and function of hospitals’, in Martin McKee, Judith Healy (eds.), Hospitals in a Changing Europe, Buckingham: Open University Press, 2002, p. 68.

Healthcare at the Crossroads: Guiding Principles for the Development of the Hospital of the Future, 2008, p. 12.

P. Boluijt, M. J. Hinkema (eds.), Future Hospitals: Competitive and Healing, Utrecht, 2005.

John Worthington, ‘Managing hospital care: lessons from workplace design’, in Sunand Prasad, Changing Hospital Architecture, London: RIBA Publishing, 2008, p. 49.

Photos

Early example of the hospital as a collage of different functional elements. Winning entry by Venhoeven CS Architecten and Itten + Brechbühl for the 2004 Netherlands Board of Hospital Facilities’ ideas competition for the ‘Hospital of the Future’

Originally published in: Cor Wagenaar, Noor Mens, Guru Manja, Colette Niemeijer, Tom Guthknecht, Hospitals: A Design Manual, Birkhäuser, 2018.